Printer Faults - Print Cartridges

Many faults in modern printers can be cleared by changing the print cartridge. In a black and white laser printer the cartridge contains something like 70% of the components that are likely to fail.

Inkjet cartridges vary in construction - cartridges for the cheaper printers contain both ink and the printhead so the likelihood of a fault lying in the cartridge is still greater.

In the early 1980s the invention of the print cartridge was crucial to making the modern idea of laser and inkjet printers possible. Laser printers were invented in 1969 at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center but they cost something like half a million dollars. By 1982 HP had the 2680A 45 page per minute machine in production - priced at $92,000 and taking several years to develop, reliability being a crucual problem. (See Jim Hall's memoirs and the Hewlett-Packard Journal June 1982 Volume 83).

Using a cartridge in the "Laserjet" (2686A) gave a fairly reliable machine that could be sold for just $3,495 in 1984. Cartridges are crucial to the modern printer, creating a mass market for what was once a specialist machine and solving most problems with an easily changed part.

There is a problem - the price of cartridges.

Concept of Cartridges

The idea of putting fiddly consumable things into a cartridge dates back some time. Cartridges originate with guns, cartridge loading made them quick and easy to use. Music cartridges originated in the 1950s with devices like the Fidelipac and Stereo-Pak which made taped music easier to handle. The Philips Cassette was a musical standard for many years.

Cartridges are "black boxes" with a defined performance and interface. The idea has been used for perfume, medicines, photographic film, gas bottles and coffee. If you want to reproduce an experience time after time try to devise a cartridge.

Some things that aren't usually thought of as such are cartridges - batteries for instance. The batteries in mobile phones and computers are essentially a cartridge holding a group of power cells. When electric cars become popular expect the manufacturers to devise proprietary cartridges.

Print cartridges are a relatively recent idea. Typewriters originally used reel to reel ribbons but in the 1970s companies like Diablo put the ribbons in cartridges. Print cartridges have several advantages:

- Users hands stay clean

- Output quality stays consistent

- Solving print quality problems often means just changing the cartridge

- Manufacturers get a revenue stream

Into the 1990s the OKI Microline 82 and 84 printers sold precisely because they used ordinary typewriter ribbon - not a cartridge. But users were becoming used to cartridges and so now almost every printer uses them.

Laser Printer Cartridges

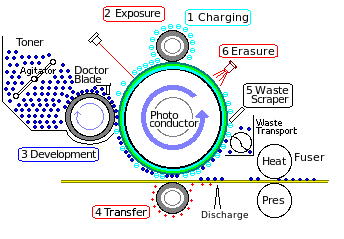

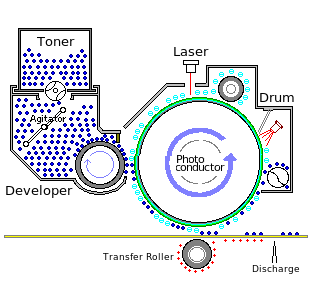

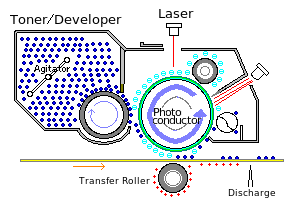

Canon claim to have invented the laser print cartridge in 1982 for their Personal Copier (PC-10) machines. Copiers traditionally had drums and developers that were part of the machine. When the components wore out a technician would be called to change them, a job that could take some time and mean the machine being dismantled on site. This wasn't practical in a personal copier. Canon solved this by putting the heart of the process, photoconductor (OPC), toner and developer in one easily changed plastic package. The same cartridge idea was used for the LBP-8 or "CX" printer and that design became the basis for many of the laser printers sold in the 1980s. For about a decade this cartridge was an industry standard

With music cartridges it generally suited the manufacturers to converge on one standard - the cassette displaced 8 track and other standards. With toner cartridges quite the opposite has been true. It is quite common to find that a cartridge only fits one or two types of printer. Using cartridge ID chips manufacturers can take a design and make it only fit one kind of machine.

If anyone had realised just how expensive and resource-hungry laser printer cartridges were going to become, it might have been possible for consumers or politicians to impose some compatibility standards on manufacturers. That might have been counterproductive however, it could have stymied innovation. Evidence suggests that what customers want is cute little colour printers, rather than more environmentally sound bigger machines. (They may say otherwise).

Cartridges are the main source of revenue for printer manufacturers, it is often suggested that they sell 20 cartridges for every mono printer.

What we have in the printer market is often called "razor and blades" marketing. The manufacturer pretty much gives away the printer but hopes to get a good revenue from cartridges. OK £200 for a colour printer may not seem like a free gift but take a look at the complexity - even in mass manufacture that's a complicated machine. It has been suggested that printer makers are selling machines for about two-thirds of the manufacturing cost as a way to get market share. There is no way to know this for sure unless the manufacturers choose to tell us. Compared with other electronic gadgets, printers generally seem cheap for what they are.

Cartridges are expensive for what they are. Toner can be bought in 10 Kilo bags for a hundred dollars or so. A mere half kilo of toner in a print cartridge can easily cost as much. (It is essentially styrene and the raw material is a couple of thousand dollars per tonne). OK the cartridge has an OPC drum and a couple of other rollers but the manufacturing complexity isn't much greater than many children's toys.

Parts and Cartridges

There are several kinds of print cartridge:

Laser printers divide functionally into about four parts: toner, developer, drum and waste bottle. There can be a user-changeable slide-in cartridge for each and at one time this was fairly common.

Most home and small office printers now use all-in-one cartridges. This type of cartridge wraps most of the parts that wear out into one easy to change assembly.

Lifetimes of the components are:

- Toner depends on the capacity of the container, ranges from 1,500 to about 25,000 pages.

- Developer usually about 100 to 200 thousand pages.

- Photoconductive Drum about 20 to 50 thousand pages depending on size and material.

- Waste bottle depends on capacity of the container, but generally about 5-10% of the toner goes to waste.

These parts and the surrounding rollers can be made into any number of cartridges between 1 and 4.

An all-in-one cartridge bundles almost all of the components into one cartridge. The obvious disadvantage is that this is quite a complicated unit and the developer and drum are likely to have quite a lot of life left in them when the toner is exhausted.

Toner Capacity.

Printer manufacturers usually sell toner cartridges with a capacity less than 6,000 pages. There are reasons:

- Toner doesn't have an indefinite life, it may "cake" after a couple of years so it needs to be used up.

- Big cartridges mean a bigger printer - and there is some competition to make smaller, neater looking printers.

- Manufacturers aim to sell more cartridges. Smaller cartridges will sell more often

A few big office printers have cartridges with much longer lives but they might not be appropriate for people who print relatively low volumes. Colour toners can be less stable than black and only last a couple of years. So if you print 3 colour pages per day a 2,000 page cartridge lasting a couple of years might be about right. Average use for a home printer is about 2 pages per day.

If you want a printer to produce 100 invoices a day, statement runs at the end of a month, print meeting minutes and advertisements that is a very different machine from a neat little desktop printer. Demands may be satisfied with a big cartridge. Where large production volumes are expected separating the components out is more help.

Photoconductor.

Photoconductors are the parts that do wear out. Amorphous silicon can in principle last for millions of pages. Kyocera's original "Ecosys" printers were based around the idea of an amorphous silicon drum that would never wear out. Problems were that the drum needed heating and dust accumulated so drums did sometimes fail prematurely. Most Xerox drums were originally made of selenium but the drum had to be taken out and cleaned every so often.

Most drums are made of two layers of polymer making a material called OPC "Organic PhotoConductor" originally invented by IBM, partly as a way to sidestep Xerox's patents. OPC materials are polymers, two or three thin layers of different materials are coated onto a drum. The top surface intended to hold the charge gets scratched, damaged and generally worn away by the waste scraper blade. The inner photoconductor surface gradually loses its response as it is exposed to light.

Barring accidents, photoconductor life is proportional to surface are so a big belt or drum should last longer than a little cylinder. Designers probably can't use a pencil-thin cylinder of OPC because:

- There would be too little separation between the pre-charge, developer and transfer rollers and their respective high voltages.

- A thin cylinder would have to whizz around rather quickly, presumably making the developer and transfer stations less reliable.

Small printers tend to have a drum about an inch in diameter that turns about four times in printing a page. It might be functional for 20,000 pages. Larger and faster printers have a drum nearer two inches in diameter that turns about twice per page. It might be functional for as long as 50,000 pages

There are all sorts of patents and techniques to make OPC life longer. The actual problem with most OPCs is that they outlast the toner charge in an all-in-one cartridge. That more or less begs for the cartridge to be refilled.

Developer.

There are several somewhat different designs of developer. First there are magnetic developers, which divide into those where a magnetic component is part of the toner and those where it is a separate component. There are also developers that work electrostatically and don't need a magnet.

Developers can last four or five times as long as the OPC. Whether the developer ever really needs to be replaced depends on the type of toner used. Developers that handle toners with their own magnetic component are can be just aluminium or plastic rollers around a magnet and they could probably last a very long time. On the other hand they are simple enough to be considered disposable.

Copyright G Huskinson & MindMachine Associates Ltd 2012