Inkjet v Laser

Until quite recently inkjets were cheaply made for light-duty home use whilst laser printers were aimed at office use. Notable exceptions were the wide format and industrial inkjets - but whilst they shared a technological basis with home injets practical implementation was quite different with complex pumps and service stations keeping the big inkjets going.

Print manufacturers like HP, Epson, Memjet and Ricoh now have inkjet printers targeted at the office market. HP, Epson and Ricoh continue to sell laser printers - and many office buyers will stick with the technology they know for now.

HP and Epson are pitching the argument as cost - their new inkjets print more cheaply that little laser printers. However there doesn't seem to be a convincing reason why liquid ink should be significantly cheaper than toner powder.

However inkjets currently do excel at producing good looking photographs. We look at the arguments for ink here ![]() .

.

Printers, Cartridges and Costs

Almost all printers use cartridges. There are two reasons:

- Cartridges simplify life for users, reducing problems and making printers user-maintainable.

- Cartridges are critical to the economics of printer brands. All brands make far more money on the cartridges than on the printer. Little printers are lovely little earners.

The printer industry is currently making printers cheaply but selling proprietary ink and toner cartridges at high prices to make up their revenues.

Buyers may guess that they will spend more on ink than on the printer, but the scale of spending might be surprising.

Cartridge Size & Cost

It is sometimes suggested that the average mono laser printer will get through about 20 cartridges in it's life. Numbers like this are no more than a rough guide because usage patterns vary, but it seems about right. Cartridges tend to scale with the printer design; indeed bigger printers often get part of their size precisely because the cartridges have a large capacity - the fuser can be made larger and longer lasting too.

- A typical small printer has a design life under 50,000 pages and a cartridge with less than 2,000 page life at 5% page cover. Manufacturers might refer to these as personal printers. In the past they would only have a USB port because they weren't really intended for sharing, but users like the convenience of WiFi so networking is likely to be built in. The operating cost for these machines is typically 3p or more per mono page. You don't really "buy" a printer this way; you effectively rent it by buying cartridges.

- Mid range printers typically have design lives around 100,000 - 200,000 pages and cartridge capacities in the 4,000 to 7000 page range. Manufacturers might refer to these as small workgroup printers; they are aimed at small offices. They will have a network port, and they probably aren't so dependent on having a Microsoft Windows PC to plug into. WiFi may be built in, but that isn't always true because IT people mistrust it. Operating cost is 1p to 2p per mono page.

- Large workgroup printers have cartridge capacities in excess of 8,000 pages for colour machines and 10,000 pages for mono machines - right up to a massive 45,000 pages in a few cases. Operating costs are 1p per page and below - down to 0.3p for some copier-style machines. These machines are typically rated for a life of 500,000 to a million pages and have user changeable fusers and transfer belts. It is not uncommon to see perfectly ordinary LaserJet 4300 printers exceed 1.5 million pages.

Scanners For Free ?

Multifunction printers with a scanner on top are sometimes little more expensive than a basic printer. Small businesses use MFPs to get copying facilities. Larger businesses can integrate the scanner into a "workflow" system. Combining scanner and printer definitely can be useful it removes the need for a copier. Printer manufacturers benefit because:

- MFPs have a lot more features for the money (mainly provided by Apps that can be upgraded).

- In being used as a copier, an MFP eats more cartridges.

At one time a digital scanner was an expensive bit of kit; several hundred pounds worth of machinery. As a separate device a fast scanner or a large device can still be expensive. Buying a scanner as part of an MFP printer usually adds between £30 and £100 to the price of a mid-range laser printer - part of that being software and a more elaborate touchscreen control panel.

Most inkjet printers are now sold in "multifunction" varieties. The scanner adds a little to the price of the printer but it makes the home user very much more inclined to copy documents - and a magazine page with solid colour is a very expensive thing to copy.

Printer manufacturers intend you to pay for that convenient scanner by your spending on ink.

Lets look at three office-quality mono laser printers from the HP, the biggest brand:

HP's LaserJet Pro P1102 is the smallest and cheapest laser printer they make in 2014. HP is a "good brand" and this general design has a heritage of success. With a street price around £65 it is a bit more expensive than some "discount" printers. There is no stated fuser life in the service manual (or that for the Canon LBP-6000 engine) but the lightweight design suggests 50,000 pages. People probably wont change the fuser, it costs more than £50. A 1600 page cartridge is £37 giving a cost per page just over 2.3p. Since the printer isn't easily repaired they are probably disposable, adding another 0.13p per page. TCO is therefore a bit under 2.5p per page. Printer life will be about 30 cartridges, over £1000 worth.

The LaserJet Pro M401 is a typical mid-range printer costing a bit under £200 (depending on the features). Again HP don't state a life for the fuser, but that will probably be what fails. Given the build, 100,000 pages might be reasonable. To reach that life, the printer will use 37 standard cartridges at a cost of about £55 each, just over £2000. People probably won't opt to change the fuser, since it currently costs just under £100 and that is too near the base price of a new printer. This £200 printer will cost £2000 during it's lifetime - at about 2p per page. The printer is now finished, so its cost gets added in; the lifetime cost was 2.2p per page.

Suppose you opted for the bigger LaserJet M602dn instead but used it in much the same way. The printer costs fractionally under £600. The small cartridges cost almost £100 (and you could buy a printer for that) but they last 10,000 pages. 100,000 pages now cost £1000 and running costs are 1p per page. Suppose your business goes bust at this point through always buying overrated equipment - the £600 printer and £1000 cartridges work our at 1.6p per page.

On a more optimistic note if your business relies on print you now have an advantage. The M602 is nowhere near the end of it's fuser life - its rated for about 225,000 pages. And when the fuser does die a plug in maintenance kit is £210 - yes the kit itself is more expensive than the M401 printer. You could buy the 90X dual pack cartridges with a life of 48,000 pages at a price of £300 which give pages for 0.625p each. That rather shocking cost of a maintenance kits works out at under 0.1p per page - so it inflates the cost of print fractionally to 0.725p.

Colour Print

Colour print doesn't cost manufacturers much. Adding colour to inkjet printers is an extra plastic receptacle in the carriage moulding and some changes to firmware and drivers. Colour cartridge sales will more than offset any cost. That is why there are (almost) no mono inkjet printers. Your "rental agreement" is to buy colour cartridges.

Colour laser printers do cost more to make, but then the user wouldn't commit to the purchase cost without a clear intention to print in colour and buy cartridges.

Colour printers tend to use significantly more cartridges. Technically it is possible to restrict yourself to using it as a mono printer, or to limit the page cover. Limits will be difficult to apply in practice. Page cover will creep up because those photo's and diagrams are the making of the document.

Computer screens are almost always colour and that puts a pressure on people to print in colour.

Adding Colour

We looked at mono printers here so far. Limiting the discussion to mono print keeps the point clear: little printers cost more to run.

Mono print is a sensible option for office work, accounts and plain text - but lets face it colour is more fun. Colour has visual impact and in a marketing and even an engineering environment that may make all the difference.

Colour is likely to have a marked impact on your printing costs.

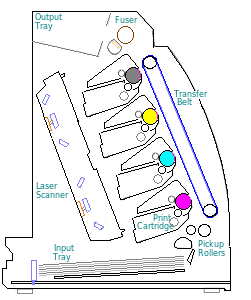

The amount of machinery increases. Where there was one cartridge there are now four. The inkjet mechanism doesn't get much more complicated - the extra cartridges just need some more interconnections. A laser printer now needs extra scanners and a belt of some kind to merge the colour separated images, so there is quite a substantial increase in complexity.

People change their behaviour as well; page-cover tends to go up markedly.

Colour magazines create a problem. We are psychologically predisposed to want that look, that heavy page cover. The problem is that the offset litho ink for a magazine is not expensive, just a few pounds per kilo. Computer ink costs a fortune by comparison. Inkjet ink and laser printer toner are priced completely differently to litho ink.

Even if apparent page cover stayed the same actual toner consumption would almost certainly rise because common colours like red are actually blends of magenta and yellow- so a bold red letterhead uses both yellow (subtracting blue light) and magenta (subtracting green) to leave that strong red. Colour inherently used more material than the equivalent in black alone.

If you must have colour avoid the big area fills the magazine art departments love. Printed by a computer device that page cover costs a fortune.

Digital print is a highly competitive market and HP products do very well. There is no great fortune to be saved by switching to Canon, Dell, Epson, Fuji-Xerox etcetera. The manufacturers are all in the same game. One "wildcard" are the recent pagewidth inkjets like the new OfficeJet Pro X series which claim to beat colour lasers on running costs. They are aimed directly at replacing older colour laserprinters like the CLJ-2600 discussed below.

It isn't clear yet whether the new printers genuinely are a breakthrough in cost. One reason we are sceptical is because we believe that ALL digital print ink prices are fairly arbitrary. The price of a cartridge has little or nothing to do with manufacturing cost; it is based on what you as a customer seem prepared to pay.

Right Size Printers

Most people are not buying their first ever printer; its a replacement market. When buying a new printer because your old one went wrong then consider why that happened. Printer faults are often predictable and result from ordinary wear on rollers and the fuser. Printer manufacturers could make more reliable printers and indeed they do - it's the model you didn't buy because of the price. However over the last couple of years you may have spent twice what you needed on cartridges.

If you are in business then a sensible way to estimate what you need is to look at your accounts system and find out how much paper you use. If its less than a packet (ream) per month buy a little printer. If its a box or moth or more then buy a big printer - it will cost more but you'll save the money on cartridges.

The message here is that printer manufacturers devise what they are offering in a competitive market that they continually study. They don't want to sell you more expensive printers - they actually want to sell you cheaper printers (charging just enough to get you committed) and then wait for the revenues to roll in as you buy the cartridges.

There are ways of running printers really cheaply by using refills - but stick to mono laser printers for that. There are bargains to be had when a design reaches it's end of life. There will be the odd brilliant buy and a few horrible dogs. Mostly, you get what you paid for.

To sum up:

- If you buy a printer for £200 or less expect to pay 2.5p or more per mono page and perhaps 10p for colour. The printer may not last very long and will be junk when it goes wrong - few spares and uneconomic to repair. Near the end of it's life it will give you some trouble and if it's an inkjet it will waste the better part of a set of cartridges as you try to revive it. Little printers have little cartridges and cost a lot to run. If you don't print much they may be good value.

- If you buy a small business printer for a bit more than £200 the manufacturer charges less for ink (or toner). But not a lot less - 1.5p to 2p per page perhaps.

- If you buy a printer for £600 or more expect to pay 1p or less per mono page. Spares are available and printer could have an indefinite life - it need not die for five years or more.

- No miracle of technology is going on here; little printers use the same toner as big printers. Cramming the laser printer rollers into a small cartridge does have some cost. However little printers cost a lot to run mainly because that is what the brands choose; if you pay less for a printer, they charge more for ink.

- Maintenance kits are not always great value and can cost more than a small printer, but then they keep a big printer running with that low copy price. Divide the cost over the extended life of the printer and its trivial - 0.1p per page or less.

We chose HP for the comparison here because they are biggest. HP's policies and prices are generally good, that is why they have enjoyed 30 years as top printer brand. If the market want's really cheap printers that can be done - but the money will come from somewhere else - expect to find cartridges are expensive.

The digital print industry is in an odd situation. Buyers focus on the up-front purchase price and ignore ownership costs. That situation can't easily be escaped. If a printer brand shifted to profit on the printer rather than the ink it's pretty clear they would sell fewer printers than their competitors, and very little ink. (Kodak tried it, they went bust).

Colour Printers

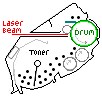

Colour printers need four cartridges: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black. There is usually a transfer belt as well. What the printers here share in common is that the belt carries the print-media. Later printers change technique a bit; the image is built directly on the belt and a secondary transfer roller pulls the image onto the page.

It is not possible for a colour laser printer to work at the same price as mono because the mechanism is more complicated so even if page cover were the same the hardware complexity would add a little.

Page-cover goes up where colour is used; magazine pages often have 30-90% cover; a full page photo can easily have more than 200% because it takes cyan and yellow to make green, cyan and magenta to make blue. Digital printer owners generally learn to tone things down a bit as a cartridge rated for 2,000 pages (at 5%) will produce just 110 at 90%. (If you want white on black, you could get one of the OKI printers that use white toner and use black paper)

The printer used as an example here is the HP Colour LaserJet 2600 series. The series was introduced in 2005/6 then re-vamped to become the CLJ-2605 in 2007/8. The printers were being sold at around £200 in 2009 but that was end-of-life. Parts are still available in July 2014.

The CLJ-2600 small business users are exactly where HP now pitches its OfficeJet Pro X series. They reckon the new pagewidth inkjet prints for half the price. (Have they decided to sell ink more cheaply.

This is a brief comparison ofthe CLJ-2600 series with the costs of running its bigger brothers. There is a much longer look at how things work here.

| Printer | Cartridge | Capacity | HP Street Price | pence / impression |

| CLJ-2600 | Q6003A | 2000 | £47 | 2.4 |

| CLJ-3600 | Q7563A | 4000 | £80 | 2.0 |

| CLJ-4600 | C9723A | 8000 | £133 | 1.7 |

| CLJ-5500 | C9733A | 12000 | £206 | 1.7 |

These were the smallest printers in HP's colour printer lineup for the time. They work similarly to the LaserJets 3600, 4600 and 5500 in general layout and operation. The printer is essentially a miniature CLJ-4600 (but lost a few points on the way).

Using the CLJ-2600 for 20% page cover will cost about 10p per page. The CLJ-4600 delivers more reliably at 2p less per page and with somewhat less trouble.

Delivering Ink

Cartridges are not all made equal.

There are half a dozen ways to get toner into a laser printer:

- Empty a bottle into a hopper. This is how things used to be done with copiers and indeed with the first Color LaserJet. 1 kilo bottles of black toner are available retail on eBay for £22 - ($20 in the US). Oki gloss toner is much more expensive - £41 for a kilo bottle - but it is an unusual product. We will return to the real price of toner shortly. The problem with ink and toner in a bottle is how well that can be handled in an office.

- Put toner into a self-opening container. The container isn't much more than a hopper with a lid that slides open as it is installed. Kyocera, Samsung and others use this approach. Kyocera TK16H original toners with a 3600 page yield retail for about £40 (but refills are about £12). Samsung have either been canny or confused here; their SCX-D6555A toner cartridges have a massive 25,000 yield and a price under £45 - at this price only one Brazilian company sells refills- the original is so cheap it just isn't worth it (drum and toner cost about 0.3p per page). The SCX-6545 is primarily targeted as a copier and a typical machine might sell for around £1500 - so that makes a difference. Both the Kyocera and Samsung printers have an "OPC" assembly that contains the developer and the organic photoconductor drum.

- Make separate drums, developers and toners. There are three or four quite distinct parts to the print subsystem of a laser printer: toner, developer drum and waste bottle. Many early printers kept the units distinct. Kyocera took this approach on all their early printers and still have it on some of the larger machines. Each part has a different life: historically a toner cartridge might deliver 10,000 pages, a drum might work for 80,000 and the developer would last for 150,000 pages. Drums and developers might be costly - £150 - but the per-page cost was trivial. If something went wrong it took some technical skill to diagnose what had happened and replace the correct part.

- Put everything in a print cartridge. Canon started selling Personal Copiers in the early 1980s and realised that it wouldn't be practical to have engineers making many home visits to diagnose faults. They came up with the idea of wrapping toner, developer and drum in one print cartridge. It is sometimes said that the print cartridge replaces 70% of the parts likely to go wrong in one user action. Canon and their computer-industry partners HP have gone on doing this for 30 years

.

. - Put things in smaller print cartridges. Smaller cartridges allow neat little personal printers that fit on an individual desk. There are problems sharing a printer, some people have to get up and stretch their legs every time they print. And there may be a problem about who takes charge of the printer, adding paper may be easy, but changing a cartridge or clearing a paper jam is not so familiar. But a little laser-printer cartridge still needs its set of rollers, so that doesn't leave much space for toner.

Copier and laser printer cartridges were quite explicitly invented to simplify maintenance. It isn't commonly appreciated that in the mid 1970s copiers were becoming big, fast machines and that the early laser printers had speeds over 100 pages per minute. The trick has been to turn a big, fast, specialist machine into something every office and home can have. Cartridges help that; they make it possible for people to solve the average issue without specialist advice. Cartridges also help because they have financed development of complicated products without an up-front purchase price of a thousand pounds.

Rather than cursing the printer brands for the £37 1600 page cartridge, perhaps we should be thanking them for making the £65 laser printer possible?

What's In A Cartridge

The Q6000A cartridge used in the Color LaserJet 2600 printers is fairly typical of the HP/Canon style small colour all-in-one cartridge. It needs a charge of about 80 grammes of toner to give 2000 pages at 5% cover (its just over 6 square meters of solid print). As we've seen that sort of thing can be bought in quantity for £5- £10 per kilo - so the toner in these cartridges bought in small quantities might be less than £1. HP sell these cartridges for £47. Remanufactured products are about £25.

The weight of the toner is a small part of a print cartridge. A typical cartridge itself weighs somewhat more than half a kilo. To be specific, the Q6000A series used in the Color LaserJet 2600 series printers weighs about 560 grammes when empty.

| plastic_case (bought in as a core) | £2-3 | 250 grammes |

| waste scraper polyurethane blade and metalwork | 50p | 68 gm |

| doctor blade and metalwork | 50p | 32 gm |

| OPC on aluminium roller | £2-3 | 48 gm |

| aluminium developer roller | 50p | 43 gm |

| hard rubber on steel precharge roller | £1 | 67 gm |

| toner feed foam roller | £1 | 45 gm |

| cartridge chip | £2.50 up | 2 gm |

The prices shown are rough and ready - got by talking to people involved in the cartridge remanufacturing game. They might pay around £6 to £8 for a kit of parts - normally the customer supplies their own used cartridge or "core".

There are no great scale economies in remanufacturing unless things can be massively centralised. Brands do have economies of scale and can make print cartridges (or more likely get them made) at well under that price.

How many cartridges would a printer like this use in it's life? It has four.

The CLJ-2600 series sold very well, at about £200 small businesses found them irresistible. There don't seem to be many left now, so unlike some of their larger relatives they didn't last ten years. Several defects killed them; the fuser and belt aren't easy to change, they had a peculiar fault that lost the alignment and could only be cured with an NVRAM reset and most irritatingly they tended to blow toner into the laser enclosure where it would build up behind the lenses causing faint print.

We haven't been able to find a stated fuser life for any of the CLJ-2600 fuser. It won't be as great as that for the CLJ-4600 which the service manual says:

Supplies Section (p 176) Image fuser kit REPLACE FUSER KIT 150,000 pages 3 50 months (Page counts are only estimations; usage conditions and print patterns cause results to vary. )

(Fusers for the CLJ-2605 are RM1-1825 and RM1-1829 available here).

The volume, weight and cost of cartridges will exceed that of the printer over it's lifetime, and quite often within a year or so. Bigger, more expensive printers tend to use cartridges with much higher capacities so the waste is lower. There are substantial industries rescuing and recycling cartridges and many manufacturers have their own recycling schemes.

Incidentally those cartridges cost just over £40 for the black and just under £50 for the colour ex VAT - and there may be delivery to pay on top; just to get an easy number lets say £50 each. A £250 printer given a new set of cartridges every 3 months (in line with expectations) could get through £4000 worth of cartridges in it's lifetime. A user could have cut running costs to less than half by opting for the bigger and more expensive CLJ-4600. Its cartridges are twice the price but have more than 4 times the yield. Experience shows the bigger printer would also be less trouble and last longer - so that would have been an environmental gain.

Real Cost of Ink

Printer manufacturers rarely if ever say what the real manufacturing costs of cartridges are. Pressed for answers by journalists or politicians they naturally stress the complexity of the product. For instance, computerworld.com interviewed Thom Brown, marketing manager at HP who says These liquids are completely different from a technology standpoint

![]() However that misses the point

However that misses the point

As we said, you can buy a litre bottle of toner on eBay for £22. We don't actually think that is a bargain: its about three times the trade price and toners are not all the same. However it is unlikely that you will get a much better price unless you set up shop as a re-filler - and many people have found that game isn't remarkably profitable.

The point is that it IS possible to buy toner for less that a tenth what printer manufacturers typically charge. It probably isn't advisable; if you are an ordinary printer user the knowledge may be distressing but it's true. Print manufacturers are bluffing when they say its all about technology. Toner and cartridge technology have advanced a little in the last ten years.

Ink and toner powder are not inherently expensive substances. Both are essentially a colourant in a transport vector. Colourant may be a complicated piece of industrial chemistry, but once the process is running it is endlessly repeatable.

Ink and toner formulation have to take into account all sorts of factors: the probability of nozzle blockage in an inkjet and drying time on the page. Electrostatic properties of toner powder and the need to heat it to the point of softening in the fuser.

However it seems fair to suggest that whilst the industrial chemistry behind printing is important and still developing so it is for paint, clothing and food dyes and indeed offset printing ink. From the layman's point of view it may be fair to compare the cost of colour in a cartridge to a tin of paint. The picture can be refined a bit later.

Specialist paints might be comparable. A 1 litre tin of Rosco Supersaturated Paint (acrylic co-polymer) can be bought online for £18.58. This is concentrated colourant; it's intended for dilution and at 3:1 dilution will give about 300 square foot coverage per gallon. If we go for the 5 litre tin it's half the price at £60 .

Comparing ink with paint might seem odd, but actually they now often do a similar job. If you want a theatrical backdrop will you paint it traditionally, or get it run off on a wide-body printer - increasingly it's the latter.

- - in the inkjet case that is a mixture of water with a bit of isopropyl alcohol and possibly glycol to give the right flow and drying characteristic. Inkjet ink must have deep and lasting colour but must not settle, flocculate or coagulate and the recipes and production processes are secret and patented.

- - for laser printers the transport vector is a plastic powder like styrene or polyester possibly lubricated by wax. Some extra additives improve the electrostatic performance. To get very fine particles manufacturers no longer use a ball mill to crush pellets, instead they tend to grow the material in solution.

Ink and toner are not inherently very expensive. The chemistry is different from lithographic inks and paints, and of course there is a rather complicated machine to deliver the material. Its all R&D costs - but mostly for the printer, not the ink.

If the printer brands choose to sell printers cheaply but make the ink expensive it is not surprising if others spot an opportunity and put clone cartridges on the market. Obviously this would completely spoil things for the brands.

Copyright protection on a straight bottle of toner emptied into a hopper would be difficult to enforce, hence there are no printers using such a straight-forward method.

Instead we get a variety of fairly complicated designs for proprietary cartridges with arguments such as zero-mess and easy maintenance in their favour and justifying the patent and copyright.

There are some additional merits.

- Using the wrong ink or even a wrongly constructed clone cartridge in an inkjet printer can clog the nozzles - either through impurities, reaction products between the inks or things like "kogation" build-up in the heads. These problems are less likely with piezo-electric inkjets like those used by Epson and Brother but we veru often hear from people who have written off a printhead.

- Laser printer tone is less particular but using the wrong toner can make a mess of a fuser; materials with the wrong melting point can adhere to the roller and cake the fuser solid. With a cheap printer that's effectively the end of the machine. With colour printers it is fairly common to find wrong toners making a mess of the transfer belt and roller (cleanable but annoying) and leading to excessive waste.

Cartridge designs and chips help ensure the right cartridge is in a machine. There isn't much doubt, however, that the key consideration is keeping clones and refills at bay.

Cartridge designs are usually just repetitions of a theme. Canon and HP tend to use all-in-one cartridges with an articulation point between developer and drum. Brother and Lexmark historically went in for separate toner-developers and drum units. Big printers almost always separate the three main components.

There has been some improvement in print cartridge performance and toner composition over time. Modern printers use lower voltages, which largely eliminates ozone production. Higher resolution printers use polyester or sytrene-acrylate or toners

If you want to use cheap refill toner then mono laser printers are least vulnerable.

Constant ChangeCarbon black is the basic colourant. Carbon as graphite or diamond is shiny. Carbon black would be shiny except that in fine powdered form the material has no coherent surface - light does reflect from surfaces but hits a particle nearby and is absorbed in a labyrinth. Carbon black is very widely used in industry not only to make commonplace things like pencils but as the colourant in plastics and paints, with a mordant to bind it as a dye in clothing and it is used as both colourant and lubricant in plastics. The major use is in rubber tyres, which would rapidly decay if it wasn't for their charge of carbon black.

The chemistry behind modern products can be quite complex to get the purities and properties required. As a crude generalisation, however, ink is black gunk mixed with water, alcohol and oil: soot vinaigrette.

Once they are in a proprietary cartridge protected by patents, trademarks and copyrights they are any price the manufacturer chooses and the customer tolerates.

How much does toner really cost? If you are prepared to buy it in significant quantities such as 10 kilo bags we think about £10 per kilo for black. Perhaps a bit more for the colours - and it does depend on the exact formulation. We mentioned the OKI gloss toner that is £40 per kilo because it's a specialist item to refill a minor brand's cartridges. Toner is available in large quantities to people who know what they are doing. Toner manufacturers simply don't want to mess about giving masses of support to the home refiller or the back street shop that doesn't know what it is doing.

Canon and Cartridges

The idea of a cartridge is quite old but interesting.

Cartridges probably originated with gunpowder; make a fiddly and dangerous material into something quick and easy to use. Toner and ink aren't usually dangerous (although toner powder can explode) but they are messy. By their very nature they are intended to stain things strongly and indelibly. Before the cartridge was invented, photocopiers were big, ungainly things used in special rooms in businesses where they would be periodically overhauled by a service engineer. We wouldn't have today's printer market at all without the simplicity and ease of use given by cartridges.

The modern idea of a printer cartridge can be credited to Canon and they apparently learned it from Kodak.

In 1962 Canon was a camera maker with a very successful product in the "Canonet" which had "electric eye" automatic exposure. Looking to strengthen sales and for new business ideas a small team led by President Takeshi Mitarai went to the US. They thought of themselves as competitors, and were a bit surprised the warm welcome they got at Eastman Kodak.

Yamaji described the Kodak visit as follows ("My Resume" on Nihon Keizai Shinbun, March 14, 1997) When we visited several of the major Eastman Kodak facilities, they bought us fancy lunches and dinners to welcome us. I asked "Why is this?". "Cameras that you manufacture are film burners" was the response. The sales of film grow exponentially in relation to the cumulative camera sales. I understood completely. It would be hard to start a new film business, but I would like to engage in consumables. Because of this experience we decided to sell all consumables when we entered into a copier business."(see Kiyonori Sakakibara and Yoichi Matsumoto "Designing the Product Architecture for High Appropriability:The case of Canon" in Management of Technology and Innovation in Japan.Cornelius Herstatt et al)

Canon were very active over the next decade or so developing a "new process" for plain paper copying that would not infringe Xerox patents. They also wanted to establish new markets and in 1982 produced the PC-10 personal copier. The PC-10 was to be for personal and family use so it wouldn't be practical or profitable to have service engineers making periodic visits. Canon made the machine "simple-maintenance and support-free" by integrating the main components of a copier that wear out into one disposable cartridge. The PC-10 was a huge success for Canon - people and businesses really took to the idea of a small, easy to maintain copier. Two years later when Canon introduced the LBP-8 (or LBP-CX) laser printer, they naturally developed a cartridge to go with it.

The LBP-CX is notable because it was adopted as the Apple LaserWriter and HP LaserJet. HP's relationship with Canon continues to date; Canon make the engines that are the basis for most of the HP LaserJet series.

Original manufacturers cartridges are invariably "chipped"; they have a small circuit board with an RFID or IC2 chip.

Print brands like to pretend the chip helps consumers. Chips record use and give some idea whether a cartridge truly came from the manufacturer and is within it's rate shelf life.

Recording toner use on the cartridge allows people with a fleet of printers to swap cartridges round and maintain the figure.

Toner levels used to be measured using opto-sensors or magnetometers. The chip might be cheaper but the instruments were part of the printer and created a bit less waste.

All the printer manufacturers say the chip protects against counterfeiting. A great deal of money rides on original cartridges so manufacturers are naturally keen to raise awareness of the possibility. The problem is that we can find only a little evidence that this occurs. Counterfeit money, watches, video-games, DVDs, pharmaceuticals, clothes and luxury goods. Cartridges not so much. When we checked (August 2014) there was no mention of it in Wikipedia. Google returns only 31,800 results to counterfeit print cartridges

, a very small haul. Almost all are HP saying "how to spot fakes" and HP press releases on seizure in Kenyan and Malaysia.

A press release for July 2014 says: ![]()

One company that is hot on the heels of counterfeiters is Hewlett Packard and in the past five years, it has conducted around 1,600 investigations across the Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) region, resulting in about 1,300 enforcement actions and the confiscation of 11 million units of counterfeit products and components.

In five years HP sells billions of cartridges, a few million counterfeits suggest a small scale problem.

Couterfeiting comes to the fore when brand names are credited with power it doesn't evidently deserve.

Counterfeits are worse than bad clones because someone is profiting from pretence.

Lets be clear what the chips are for: they make refilling difficult. It isn't impossible; refillers can pay Static Control, Uninet or several others for chips that will fool the printer.

Along with the engine goes the cartridge mechanism. These days it is naturally ‘chipped’ to fit the brandnames engine. At one time cartridges would fit either machine.

For a while in the mid 1980s it looked as though the world could almost adopt one standard cartridge - most laser printers were based on a Canon cartridge. That would presumably have been good for consumers because competition in cartridge production would hold down consumable prices.

Standard cartridges not have suited the printer makers. Cartridges would be commoditised and low-cost compatibles would dominate. Canon has quite a lot of competitors, notably Epson, Ricoh and Brother as well as HP. Each generation of printers brings some technological advance and a change in cartridge design. A look through any remanufacturers list will show hundreds (often thousands) of mutually incompatible cartridge types.

Canon and HP naturally adopted the same business model of using cartridges when they produced the first inkjet printers. Altogether there are about 85 printer manufacturers and nearly all of them use cartridges - it's simply too good a business model to miss out on.

Faced with the price of a new cartridge, people commonly complain about being "ripped off"; we do ourselves. But we know what the business model is and how it works.

Manufacturers like cartridges, it gives them "appropriability" to use the economists term. It means they get a strong measure of control over the consumable revenues. Camera makers and even coffee machine vendors put their products in cartridges. It wouldn't be a surprise if car makers put oil in cartridges and if electric vehicles succeed what's the betting the batteries will be in cartridges?

A £17,000 cartridge - that will be eye-watering.

Copyright G Huskinson & MindMachine Associates Ltd 2012-2014